Reading in Public No. 58: The disappearance of literary men DOES concern me

Kind of...and not in the way you think

Today’s post is a little ranty and a little rambling. I’m short on time this week, but I needed to get this all out so I set a timer and did what I could. This is a subject I will certainly be returning to. More coherent thoughts forthcoming.

We should expect men to connect to books by and about women on a level of shared humanity rather than putting The Handmaid’s Tale in front of them and saying look how tough these ladies have it.

My most popular and widely shared newsletter ever was about the problem of boys (and men) not reading books about girls (and women). This is a topic I care about deeply, especially after teaching in a single sex environment. So when this conversation bubbled up in two prominent spaces this week, you better believe I was inundated with emails, texts, and DMs making sure I’d seen it all. And I love all of you for that! Thank you for seeing and supporting my passions.

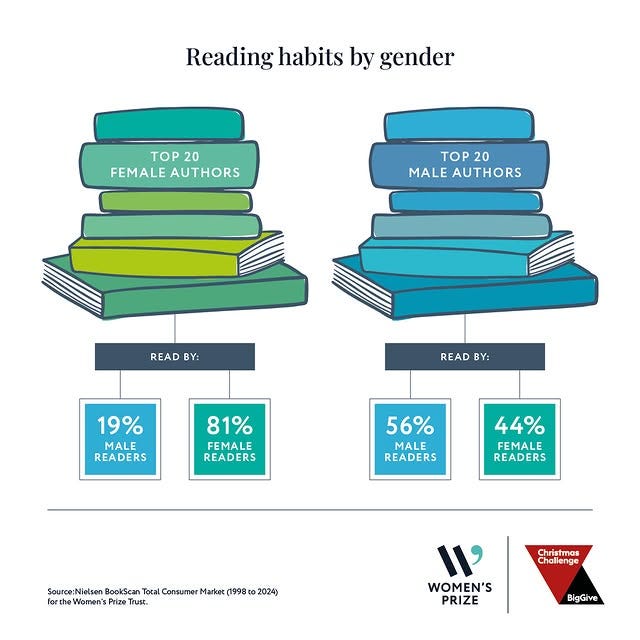

The first was an Instagram post shared by the Women’s Prize on December 6th revealing that, according to surveys, the top 20 bestselling male authors have a readership that is 56% male and 44% female while the top 20 bestselling female authors have a readership composition that is 19% male and 81% female1.

We are not surprised by this, are we? As mentioned, this is something I think about all the time and yet (or perhaps because of this) my expectations are on the ground. I would be willing to bet that if you took classics and crime authors out of the list of 20 top selling authors used to inform this data2, the percentage would indeed be lower than the cited 19%.

One commenter on this post wrote, “Could be that female authors write specifically for women, make [sic] authors write more universal subjects.” I am so glad that somebody wrote this because it is saying the quiet part out loud. Of course the problem is not that women only write about women stuff. But the perception that women write for women and men write for everyone is foundational to these readership discrepancies. Breaking news: the cis/het, white male experience is viewed as universal, while everyone else is an other.

The Women’s Prize report was illuminating, but the real instigator of this piece was an op ed in the New York Times titled “The Disappearance of Literary Men Should Worry Everyone” by David Morris, a creative writing teacher at the University of Nevada (the link is a gift link if you care to read it). First of all, I want to say that the discrepancy between girls’ and boys’ success in the contemporary educational landscape truly does worry me. I am not someone who thinks that because white boys had it good for so long, we should be unconcerned at their current floundering (though trust me, I understand that instinct). But as Jason Reynolds put it so perfectly in this episode of the The Stacks, there’s a difference between connecting with and catering to, and I worry that—even as it bends over backwards to act as if it is not—this article and others like it are advocating for catering to boys.

The presupposition of Morris’s piece is that men reading more literary fiction would aid in solving some of our societal problems. As someone whose business is literally named FictionMatters, I’m inclined to agree or at least want to agree with this. The men in my life who—IRL and online—are wonderful, empathetic, politically active people. But as a brilliant NYT commenter pointed out, “Men used to read and write a lot more. They owned the territory. Were they better men? No is all I come up with.” Reading in and of itself cannot fix anything. What and how we read matters.

One of the key problems with this essay is that when it does concede that men ought to be reading books by women, it seems to insinuate that men should read these books to learn about the experience of being a woman. I think empathy for experiences outside of our own can indeed be a byproduct of an active and extensive reading practice, but when we treat books by anyone other than a white man as singular to a specific identity, we continue to deny the full humanity of these stories. We should expect men to connect to books by and about women on a level of shared humanity rather than putting The Handmaid’s Tale in front of them and saying look how tough these ladies have it3.

Contained within the question of universality, another problem with this op ed is that dances around the fact of race. Morris cites Joyce Carol Oates’ 2022 tweet in which she claims that editors will no longer look at manuscripts by not-yet-established white male authors. He then acknowledges that the publishing world remains too white but that we should still be concerned about “the fate of male writers.” But this is an intersectional issue, and this really made me wonder if the article is primarily concerned about white male readers and writers. Just this year debuts by male authors of color included the breakout success of Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar, the rapturous reception of Rejection by Tony Tulathimutte, and other standouts like Ours by Phillip B. Williams, God Bless You, Otis Spunkmeyer by Joseph Earl Thomas, Fire Exit by Morgan Talty, and Sky Full of Elephants by Cebo Campbell. These books may not be on the NYT bestseller list, but—let’s face it—very very few literary fiction lands on that list at all. They are, however, on prize lists and as much a part of the cultural conversation as literary fiction debuts by women this year.

Without saying it directly, then, this piece seems to be primarily suggesting that white men are (or have come to see themselves as) excluded from the literary world. I can’t speak to what’s happening in the realm of writing and publishing. I have no idea which manuscripts are being rejected or dismissed or who is showing up for creative writing seminars. I do believe Morris when he writes about the demographic shifts in his program.

But in terms of readership, the problem, to me, is that white men need to learn—as all the rest of us have—to connect with stories outside of themselves. And I’m not saying this is an easy problem to solve or as simple as a shift in mindset. From picture books to popular middle grade fantasy to the books assigned in high schools, our culture allows white boys to see themselves as the universal, the baseline, the primary human experience. And this doesn’t even get into representation in films, television, video games, etc. Of course men expect to see themselves reflected and centered in their entertainment. Of course they aren’t naturally gravitated towards books by and about women. We need a radical overhaul in how we bring up our young readers if we’re going to tackle this issue. We must expect boys to relate to the universal aspects of all stories.

And look, this is all sticky and nuanced, of course. Personally, I think the whole concept of universality can get us into trouble. But connecting with books across gender, race, sexuality, etc. on a human level should be a baseline expectation. This is not the same thing as pretending that, say, I as a straight white woman can fully understand another experience just by reading about it or that we should ignore real differences in lived experience in favor of what we have in common. No one’s experience is universal. Everyone’s is human.

And this problem—the problem of men feeling excluded from the literary world, the problem of 80% of men most likely unconsciously avoiding books written by women—is rooted in the fact that one group of people is granted universal status while everyone else is not. It’s both simple and infinitely too complex to be diagnosed, let alone solved, in a single op ed or newsletter. To fix the crisis of a dearth of literary men, we need to convince men that their experience is not universal and to see the connected humanity of stories outside their singular lens. I wish us luck.

This data is pulled from the 2023 Nielsen BookData commission. The Women’s Prize report does not describe methodology and I do not have information as to whether genders outside the binary of male and female were included in this study.

Not all 20 authors are named in the Women’s Prize report but they do say the list included Jane Austen, Agatha Christie, Martina Cole, and Taylor Jenkins Reid. Among the 20 top selling male authors were J.R.R. Tolkien, Charles Dickens, Matt Haig, and Stephen King.

While Morris explicitly says that he thinks men should read Sally Rooney and Elena Ferrante, the only book by a women writer he mentions assigning is The Handmaid’s Tale. I am glad Morris assigns this important work, but I think it’s a problem if one of the only books men read by and about women is a politically charged book about reproductive rights. They should read it, yes, but they we should not model that we only read books about women to understand this type of dystopic suffering.

This is hitting the nail on the head: “Of course the problem is not that women only write about women stuff. But the perception that women write for women and men write for everyone is foundational to these readership discrepancies.” 👏 And it’s the same bias for race too.

Appreciate this ongoing noodling of the issue, Sara! Aligned, I was listening to (another) podcast recently about “are men ok/what is wrong with men?” where they mostly meant cis/het white men and it has all been making me a bit frustrated that these conversations seem to be leading us in a circle back to these same men being at the center? I feel frustrated that while the problem seems important to identify that it’s hard to talk about it without feeling like we’re still putting this demographic at the center. Discussions like yours are nuanced in that, they’re hoping to encourage the centering -or at least exposure- (through reading) to other identities but we’re still having to focus on the dominant demographic in the process. It makes me feel a little batty 😵💫 I don’t really have a question, and I definitely don’t have an answer. Maybe I just dream of a world where we don’t have to constantly consider the white cishet male of it all???