Reading in Public No. 54: Boy books, girl books, and the politics of reading

Or why we should expect boys to empathize with Jane Eyre

This week I became enraged after listening to an episode of The Daily about the gender divide among young people in this election. The episode is now behind the paywall, but, to summarize, 18-29 year olds are extremely divided by sex when it comes to who they will vote for in the upcoming election. The Times did extensive polling and then talked to some likely voters to explore this gap further. The gist of their findings is that young men are supporting Trump because they have lost the script on what it means to be a man today and feel that Trump’s policies and personality offer a more clarifying path. The young women feel threatened by the loss of reproductive rights as well as disgusted by the things Trump has said about women. After exploring this, the show played clips with the reporter asking the women if they could empathize with why these young men are voting for Trump. As soon as it happened I knew what was, or rather what wasn’t, coming. Because, no, The Times did not subsequently ask these men if they could empathize with their female counterparts. If they did ask, they didn’t include it, which just might be worse when it comes to the point I’m making today.

Here is why I knew this was coming. Because in my experience teaching high school English, it was made abundantly clear to me over and over and over again that while no one gave a second thought to asking girls to read books about men, the idea that boys would be able to connect to stories about girls and women was dismissed outright.

For six years I taught high school English at what is, to my knowledge, the only co-divisional high school in the United States. This is a school that was one school, under one leadership, but in which boys and girls took separate classes in separate buildings. Setting aside the issues with single sex education for today1, my time at this institution was a fascinating up close look at how we view sex and gender differences in education. And it proved to me that it is an accepted cultural norm to assume that girls can and will relate to the male experience but boys can’t and won’t relate to the female experience.

To be sure, the girls didn’t read that many books by or about women either. When I first started at this school the only book written by a woman in the American Literature curriculum was My Antonia by Willa Cather which is—you guessed it—primarily about a man. The British Literature curriculum only included Frankenstein (by a woman, about a man) and Jane Eyre. Our division did offer a Women in Literature class, which I had the honor of teaching2. Women in Literature was not offered in the boys division for my first five years at the school. When we opened it to the boys in my final year, one boy signed up3.

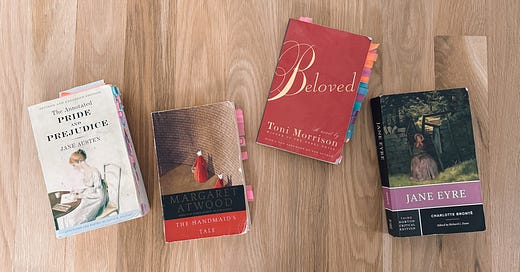

Young women are expected—without a thought, without even consciousness of it—to understand why Holden Caulfield feels isolated and vulnerable. At the same time, there is a presiding belief that it is basically impossible to get boys to enjoy books with women protagonists. Young men are not, in the same way, expected to understand the plight of Jane Eyre and the true terror that comes from being completely dependent. They are not expected to understand the precarity of the Bennet sisters’ situation, who—if they do not marry—face complete and utter destitution. They are not expected to understand the complete horror of the sexual violence Sethe experiences and the gut-wrenching choice she makes when School Teacher approaches her home. These very ideas are a joke to many. I mean this literally. I have heard English teachers scoff at the very notion that boys should have to read Jane Eyre or are mature enough to handle Toni Morrison.

We have, in our literary culture, decided that men and boys should not be expected to relate to women within the pages of the book. While we believe that any reader no matter their identity can relate to stories of white men, experiences outside of those are othered.

This becomes so natural that when I read books like The Great Gatsby and My Antonia with my girls, their tendency was to connect more deeply with the male protagonists. This was fascinating to me because these are books with interesting and complicated female characters whose stories are told by their male narrators. That concept was not something my students could readily latch onto—they took the male narrators’ perspectives at face value, because they have been implicitly taught over and over that the male experience is universal and the one worth paying attention to. But how could they not? With a literary canon filled with Holdens, Winstons, Nicks, and Hucks, they are sure to easily identify with the men and boys they see on the page.

Of course this is an intersectional issue, and though the focus of this essay is sex and gender, I do not want to diminish the other ways and other reasons young people are marginalized by the books we hand them. There are many readers who see themselves represented in the pages of books much more sparingly than white teen girls. I, as a straight white woman, have the privilege of occupying a sort of universality of womanhood. It is very easy for me to find stories that reflect my experience and to resonate intimately with the books I read. And yet what I have seen as an educator and reader is that I, as a woman, am fairly well equipped to go on to read and resonate and empathize with stories outside of my own experience. This is not because women are inherently better at this, but because I, like all women in the Western world, have grown up constantly being asked to understand and empathize with men. We already know how to occupy the position of the other.

And we know this is true outside of the classroom because of how the rest of the book world operates. In the publishing world, there is an entire category of Women’s Literature. The reason there isn’t Men’s Literature isn’t because publishing doesn’t care about men, it’s because Literature without any qualifiers—so called universal literature—is for men. It is a well-known tenet of children’s book publishing as well that while girls will read books with boy protagonists, boys are much less likely to read books about girls. There was a recent article in The Bookseller that asked if the publishing world has abandoned teen boys. I saw this shared repeatedly and emphasized by many readers I know and trust. I don’t have teen sons and I trust the readers who tell me that this phenomenon is real. At the same time, we are doing a disservice to everyone if we unquestioningly accept the belief that boys will only read about boys.

It does a disservice to boys because it is insulting and limiting. Do we really want to operate under the assumption that boys do not have the empathy, imagination, or emotional bandwidth to see the world outside of their own perspective? This is so sad to me and not the world I want the kind, curious, caring boys I know growing up in.

And of course it does a disservice to the rest of us because if young white boys in schools are not asked or expected to connect with other experiences in books, when will we begin to teach them how to connect with other experiences in the real world? Consider, for example, that men aren’t citing abortion and reproductive rights as a primary voting concern at nearly the rates women are4. Even when young men cite the ability to provide for their wives and family as their top concern, they are prioritizing their position—their main character position—in the lives of the women around them rather than listening to what matters most to those women. This is why we hear again and again from politicians in every party urging men to think about the lives of their wives, mothers, daughters and sisters5. We don’t expect that men can empathize with women at large, so we beg them to consider those closest to them.

Readers often talk about how reading promotes empathy, and that is true. But often I think we talk about this as if when we read a book with a protagonist from a character outside our own demographic, we automatically can access empathy for that other experience. I read this, and now I feel this, etc etc. But that’s not how it works. Reading creates empathy because it forces us to see the world from someone else’s position and decenter ourselves again and again and again. It is a practice in imagination that must be practiced again and again and again. It works when we do this over and over and therefore develop the ability to think outside of our own centrality. When your position has been defined as universal, you do not practice this at the same rate as the rest of us.

I’ll end with something I wish I didn’t have to say: please do not “not all men” me. Of course many men read books about women. Many men write books about women. I taught with male teachers who were great at fostering connections between their students and the books they taught, regardless of gender. I spent time with male students who clearly valued the opportunity to engage with perspectives outside their own. Many men can and do empathize with women. The problem is not so much that individual men will not do this—although of course we all know that many men will not—it is that we have made it so culturally permissible for men to not see outside their own perspective, that, as evidenced by last week’s Daily, it doesn’t even occur to us to ask if they can empathize with women.

Over a hundred years ago in A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf wrote about the long shadow of the male “I” that looms over literature. I don’t know what it will take to finally cast aside that shadow or to endow writers who aren’t straight white males with that same commanding “I.” But I do believe that putting an Austen, Brontë, Cisneros, Erdrich, Morrison, or Ernaux in the hands of our boys is a good place to start.

To support Reading in Public and the FictionMatters newsletter, consider upgrading your subscription today.

I will say I loved teaching all girls and the research bears out that all girls education is very good for girls, but all boys education is not so good for boys.

One thing I am most proud of in my time as a teacher is growing this senior elective from being offered one semester with 12 students enrolled to being offered twice each semester with classes as large as 28 students.

I worked with wonderful, passionate teachers at my school. I tell these stories not to condemn a particular place or people, but to offer an example of how ingrained these ideologies are.

“Women attach at least slightly more importance than men to all seven issues rated, but the gender gap is particularly wide for abortion. About half of women (51%) versus a third of men (32%) rate it as extremely important to their vote.” (Gallup)

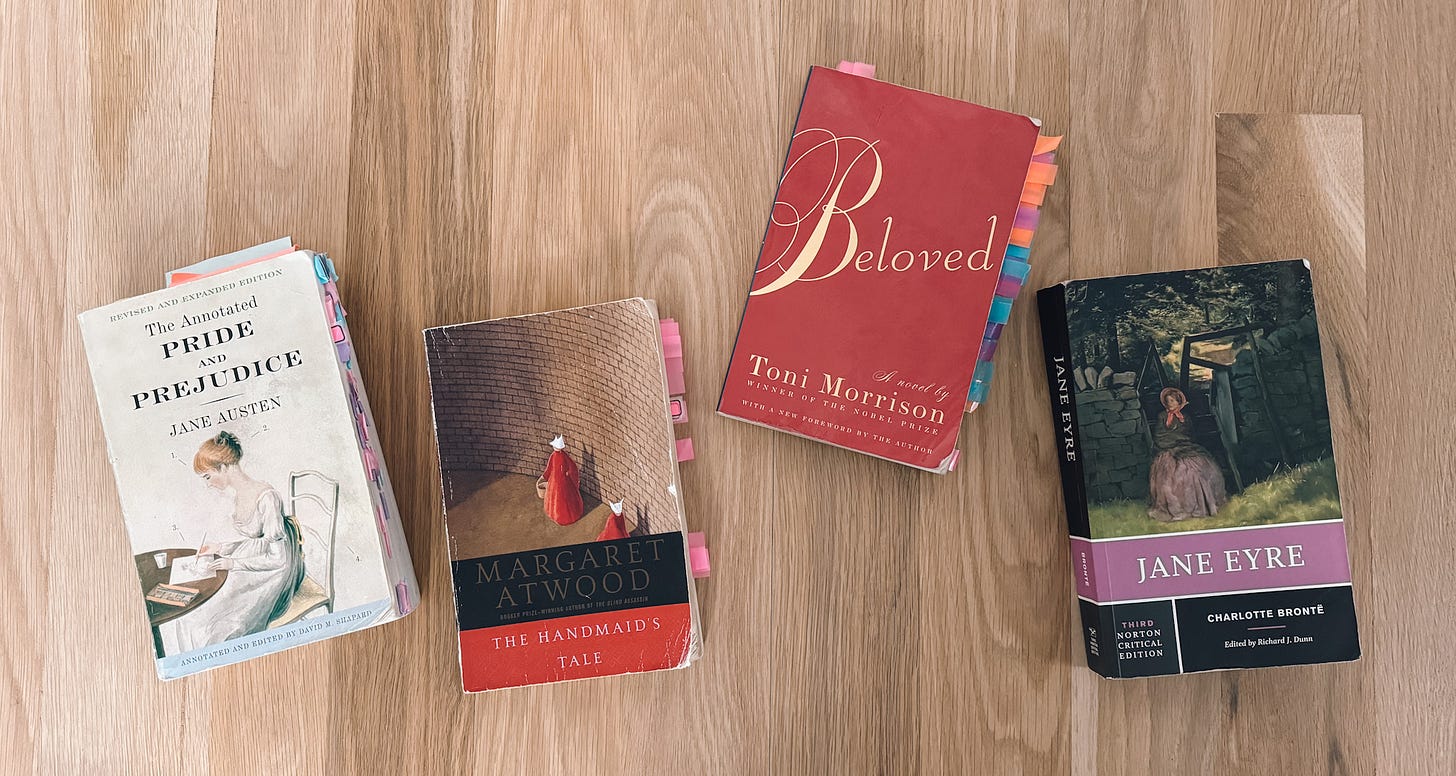

Michelle Obama did this, of course, masterfully in a recent speech. She was able to simultaneously convey a plea for men to think about the women in their lives and articulate how exasperating it is that women must make this kind of plea. She is my rhetoric queen.

Sara: This is probably my favorite piece you’ve ever written!!! Sadly so true and so elegantly expressed. Just wonderful.

I love this and have so many thoughts about all of it. I mostly just really love your talking about the practice of reading outside of ones self and how it trains you to see outside of yourself in the world. That is the power of storytelling broadly, and for us book people, books more specifically.

And all of this goes for film, TV, and event sports. We're seeing it now in the WNBA especially.