Reading in Public No. 76: If you don't have a complete sentence, you don't have a complete idea

One simple way to think more deeply about books

Before I get to today’s newsletter, I have a request! I will be traveling quite a bit this summer and while I may take an entire week or two off here and there, I’m hoping to prep some newsletters in advance. If you have a reading question you’d like me to answer, a conundrum you want help solving, a type of book you’d like recommended, or a topic you want me to explore in Reading in Public, please share those with me in this form. Your input will help me get pieces drafted early and make sure I’m keeping my newsletters interesting and informing to you. Thank you!

When you teach writing to high schoolers, you sometimes rely on aphorisms and conventions that aren’t always true but do help get an emerging writing to a deeper level of thinking. Remember, for example, when your high school teachers wouldn’t let you use “I” in your papers only to get to college and see the first person used fairly regularly in research and theory? That was because learning to write without relying on “I” pushes a writer’s skills, requires them to consider what is fact and what is opinion, and forces students to explore less familiar sentence structures. Once you practice all of those things, you get your I’s back.

Another phrase I used frequently in my classroom was “if you don’t have a complete sentence, you don’t have a complete idea.” Is this always true? Of course not. But it’s a genuinely helpful way to get students thinking more deeply about a book, especially in terms of identifying themes. Today, I thought it would be fun to explore that concept here.

The “complete sentence” aphorism most frequently came up when I was conferencing with students about papers in the early brainstorming stage of writing. This is the point when students were trying to identify themes to explore and shape those themes into an argumentative thesis. Often students would tell me they wanted to write about themes like identity, nature, gender, and the American Dream (I did teach The Great Gatsby, after all). When students suggested these kinds of topics I’d ask them to try to turn that topic into a complete sentence because without a complete sentence, they didn’t have a complete idea.

Now, you might be wondering how often I got the full sentence response: “this book is about the American Dream.” The answer is a lot. And to these students, I’d gently prod, That’s not really what I mean. What do you think the book is saying about the American Dream? Can you answer that in a complete sentence?

Often there would be no initial response, but then…light bulb moment! A theme constructed as a complete sentence, a theme that answers the question “what is the book saying about X topic,” is already a thesis. It’s argumentative. It’s offering an interpretation. It’s a complete idea. Usually my students weren’t able to come up with their final arguments or fully realized ideas in these initial conversations, but they would start asking the questions required to move them from a fragmentary thought about a book to a complete (and arguable) idea.

I think this is a great exercise for all readers, and it’s something I find myself asking myself constantly as I’m reading. For those of us not writing analysis essays for the eyes of educators, this practice is not about finding the right answer, or even an answer. Instead, it’s about thinking more deeply about a book by trying to understand the way it works and what it’s saying about the human condition. Big Idea words and phrases like identity, motherhood, ambition, redemption, doubt, longing, etc, are a start, but they are not complete ideas.

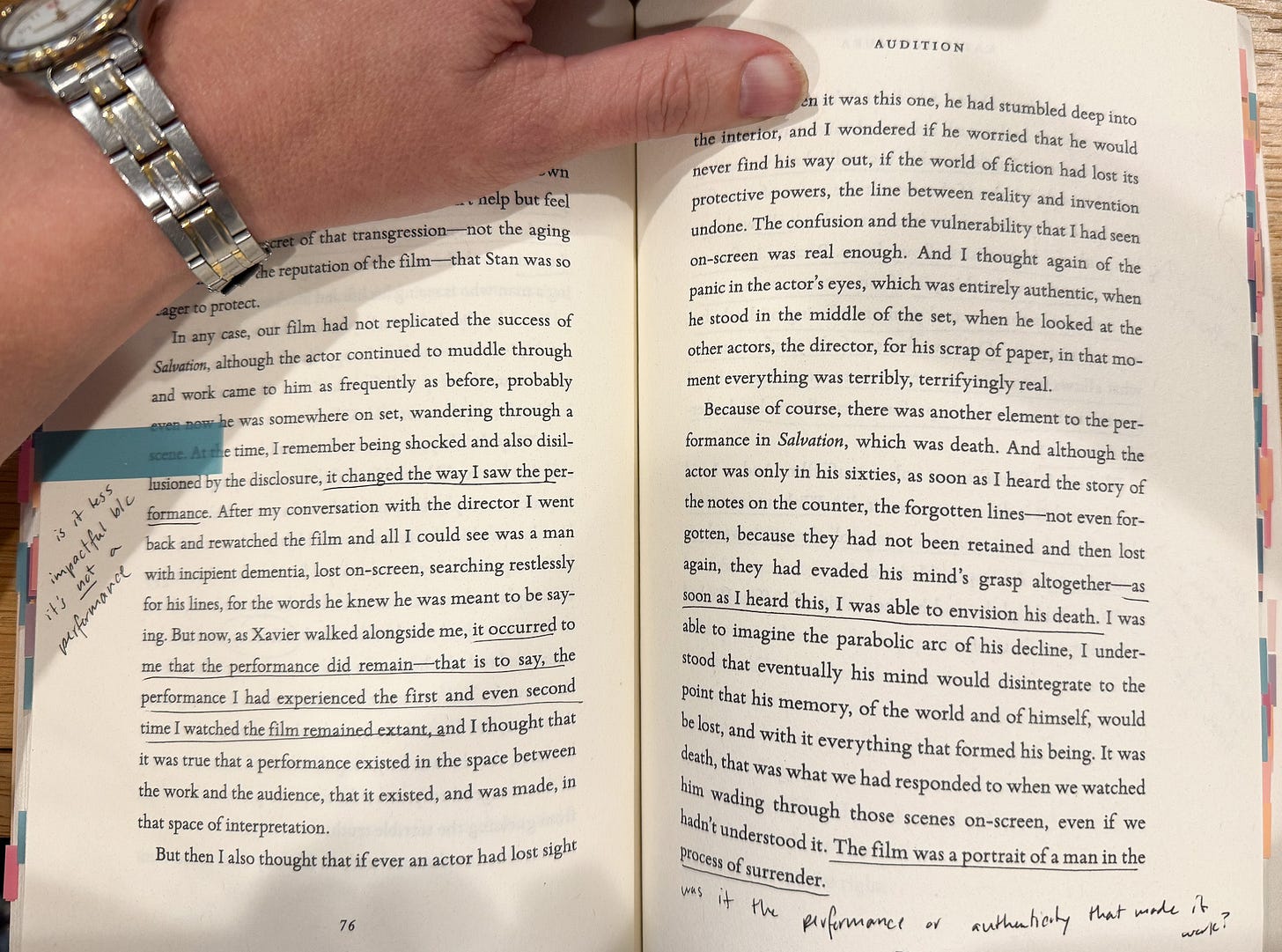

Here’s an example from current book discourse. I have heard so many people (including the author herself and probably me!) say that Katie Kitamura’s Audition is about “the roles people play.” But that isn’t really very interesting because it’s not a complete idea. The complete idea would be mining into what we think Audition is saying about the roles people play. What are those roles? Who casts them? What does it mean to “audition” for these roles? What happens when we abandon the roles we’re assigned? Attempting to answer questions like these—in complete sentences—is a more challenging critical thinking exercise and allows us to actually move towards a theme.

To be clear, this isn’t a criticism of using broader thematic terminology in book reviews. I still use phrases like “this book explores themes of identity” all the time in my mini reviews. In fact, standard book reviews probably aren’t the best place to get so specific about thematic interpretations1. I often avoid this kind of specificity because I think the fun of reading is to discover our full sentence answers for ourselves! Gleaning what I believe a book is saying about identity or the roles people play (or any idea) is a large part of why I read, and I wouldn’t want my reviews to take that experience away from another reader.

The point here is not so much how we phrase things in off-the-cuff remarks or evaluative book reviews. Rather, I want to suggest that aiming to construct our interpretations of literary themes in complete sentences is—simply and radically—an opportunity to think. So often readers move through books by gliding over the surface rather than taking the time to get deep. And now, resources like Storygraph AI summaries spit out neat lists of three theme words for seemingly every book on their site. But there aren’t right answers when it comes to literary analysis and the messiness and depth that comes from asking deeper questions is what makes literature human and important.

So here’s an invitation or an exercise—however you choose to see it. Whatever book you’re reading right now, identify one of the Big Ideas the book seems to be grappling with and then ask yourself: what is this book saying about that? Think it through until you arrive at an answer in the form of a complete sentence. If you’d like, drop your sentence in the comments below! I’d love to see your thinking, and I can guarantee it will be a quick, simple, and transformative way to dig deeper into whatever you’re reading now.

For questions, comments, or suggestions, please don’t hesitate to reach out by emailing fictionmattersbooks@gmail.com or responding directly to this newsletter. I love hearing from you!

This email may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase through the links above, I may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you.

If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, please forward it to a book-loving friend. That’s a great way to spread bookish cheer and support the newsletter!

Happy reading!

Sara

This might be part of how I personally distinguish between a book review and criticism. To me, a review evaluates a book while intentionally leaving space for the reader to eventually interpret themselves, whereas criticism offers both evaluation and thorough interpretation.

A great way of thinking about ideas in books! I also tend to be more generic in my book reviews so as to let a reader discover things about the novel on their own; but I truly love criticism (like in BookForum) for how deep it dives into themes and ideas within a novel.

Love this idea. I’m reading Lear and pondering nothing, which seems to come up a lot. So maybe my sentence is a question: when is nothing actually something?