Reading in Public No. 61: Jeremiads and the American imagination

When a classic American rhetorical practice is used to terrifying effect

I had fully intended to avoid all inauguration coverage yesterday, but debilitated by a sinus infection and raging headache I didn’t have the strength to fully resist. I ended up consuming a little bit of the day, which was much more than I wanted. I didn’t watch Trump’s inaugural address, but I did succumb and read the transcript. As a former American Literature and AP Language and Composition teacher and someone who believes in the power of language, I’m always interested in the rhetoric politicians use to craft their narratives and persuade, so I often read big moment speeches. While I’ve found every Trump speech that I’ve read or listened to as rhetorically objectionable as they are morally repugnant, something did catch my attention in yesterday’s remarks. Trump was (undoubtedly unknowingly) performing the well-tested, often used American staple: the jeremiad.

Jeremiads are speeches in which an orator lays bare a series of grievances or social wrongs and juxtaposes them with their own ideal vision of society. Named for the Jeremiah who is said to have written the series of mournful laments that became the Book of Lamentations, jeremiads began as a style of homily in which a pastor would compare Biblical ideals with earthly realities to inspire parishioners towards a vision of Christian community. According to critic Sacvan Bercovitch, such speeches are particularly effective at unifying a community or a subgroup because they “create tension between ideal social life and its real manifestation.”1

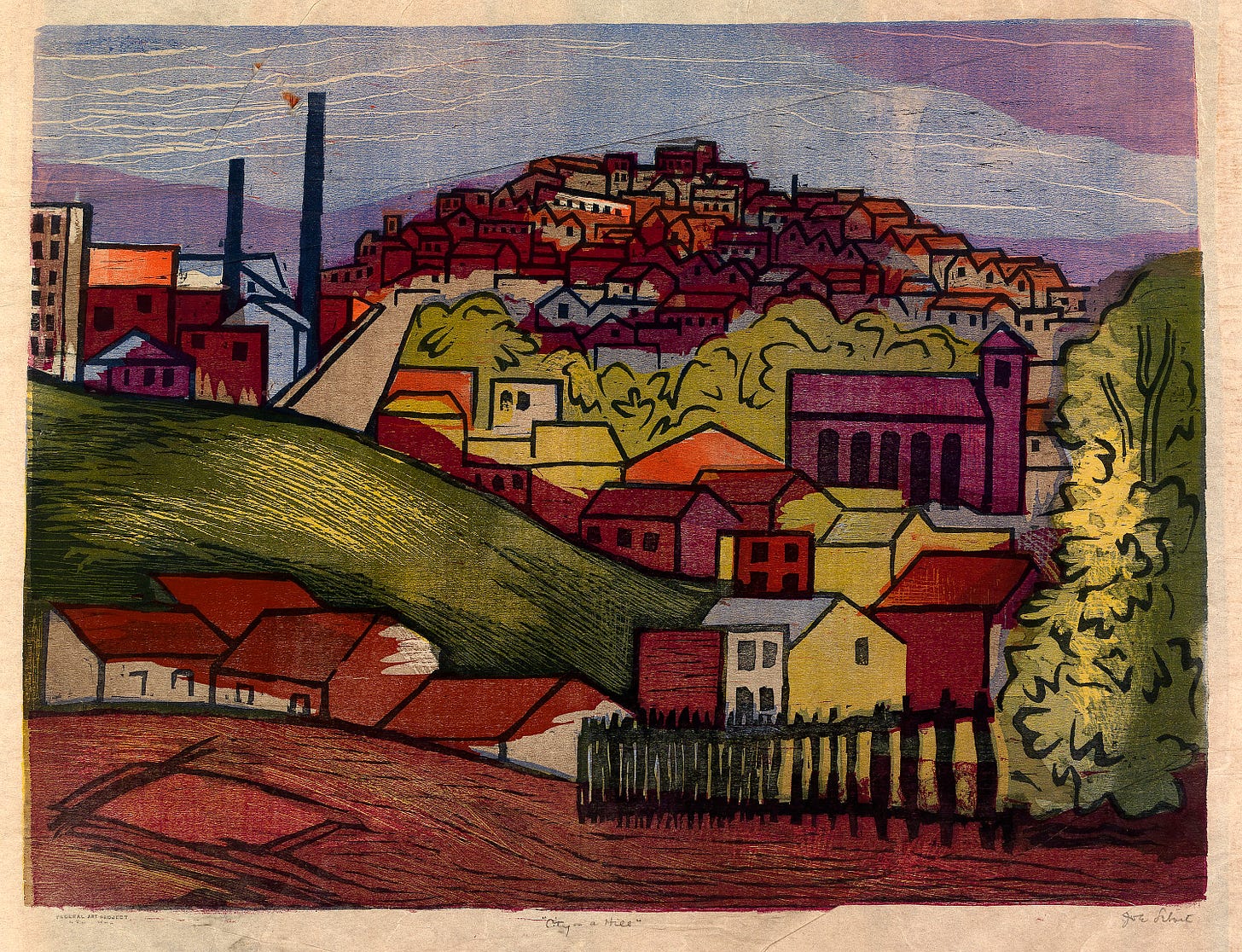

These speeches became mixed with the political in the earliest days of the American colonies as Puritan pastors would use this rhetorical framework to layout political and social expectations for their settlements, bolstered by a fervent adherence to Christianity. We see this as early as 1630 when John Winthrop gave his long-reaching speech “A Model of Christian Charity” on a ship bound for the the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In this jeremiad, Winthrop expands upon the persecution the Puritans had faced and the perceived dangers that lay ahead. He then goes on to make a proclamation that still clouds our American worldview today, suggesting this new colony “must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill.” While Winthrop spoke primarily of the shame that would come upon the Puritans if they were hypocritical or unfaithful to their beliefs, the idea that “the eyes of all people are upon us” has come to be part of the ideology of American exceptionalism and the concept that the world looks to us as a beacon and a model.

Presidents throughout history have used both the jeremiad form and allusions to “a city upon a hill” to make the case for their agendas. Kennedy, Reagan, and Obama were all fond of the jeremiad—and all three allude to Winthrop in their Farewell Addresses2.

To me, what sets Trump’s rhetoric apart is twofold. First, he revels in his airing his grievances—and many of them are personal. Rather than the mourning and passion behind something like Obama’s memorial speeches after shootings Charleston and Tucson or even Reagan’s straight-forward depiction of a decline in American patriotism, Trump lingers on his perceived grievances—it seems to be his favorite thing to do rhetorically. While this is repulsive, the second difference is much more frightening. Historically, American jeremiads have built their utopian vision on and appeal to a larger power. a moral ideal, or an ethical obligation. While there is much to disagree with in any one of them, there was a values system constructing the concept of righteousness and a belief that the constant pursuit of an ideal is what constituted this “city upon a hill.” For Trump, however, there is no values system or moral ideal or ethical obligation which to appeal. Rather, he insists that it is only he who can usher in this supposed “golden age” of America. This is a significant and scary turn in American rhetorical tradition, and one that is important to note.

The jeremiad has been with us since this country’s inception—even the Declaration of Independence has the shape of a jeremiad—and so it is unsurprising that our leaders continue evoke this form at pivotal political moments and the juxtaposition of the real with the ideal will always be an effective rhetorical strategy. As these next four years unfold, keep an eye out for the grievances and for the way Trump and those around him try to rhetorically reshape the idea and ideal of America into their own image. While being on the ground serving our communities and combatting these policies is what matters most, the language of it all matters too. As Winthrop shows us, it can have centuries-long effects.

I’m considering writing more posts like this in a series exploring the ways American literature has shaped and calcified American ideology. If you enjoyed today’s post and are interested in the ways classic American stories continue to influence our politics and every day lives, please let me know!

For questions, comments, or suggestions, please don’t hesitate to reach out by emailing fictionmattersbooks@gmail.com or responding directly to this newsletter. I love hearing from you!

This email may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase through the links above, I may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you.

If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, please forward it to a book-loving friend. That’s a great way to spread bookish cheer and support the newsletter!

Happy reading!

Sara

Aufses, Robin, et al. Conversations in American Literature. Bedford/St. Martins, 2015.

The most powerful jeremiad I’ve ever read was not given by a president, but by Frederick Douglass in his incredible speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July.”

Wow Sara - this made me feel like I was back in school (I love school) in the best way! I loved learning about jeremiads, and your detailed contextualizing is lucid and fascinating. Thank you!!

Sara: I felt like crap and had a massive headache, but here is a brilliant and insightful piece with historical relevance on current events.

The rest of us: Eating potato chips, drowning sorrows.

(Thanks, lady! So good.)