Reading in Public No. 80: Considering themes and exploring purpose (Reading Well Challenge #2)

The midpoint of our one book reading well challenge

I am so thrilled at how many of you are joining me in for this spur-of-the-moment challenge to slow down and read one book well. We’re at the halfway point of my posting timeline, but it truly doesn’t matter if you’ve already finished your book or have yet to start—this can be done on your personal timeline. This challenge is all about going back to the basics and thinking about what reading well looks like for you. I’m just sharing my reflections and offering some food for thought along the way.

Today’s post is split into two parts. In the first, I’ll share some of my notes and reflections from my attempt to start strong with my chosen book, Black Water by Joyce Carol Oates. In the second part, I’ll offer some guidance on wrestling with theme—that ubiquitous English classroom word that might haunt or annoy you as a grown up reader—and some tips on discerning what your book is trying to do.

Let’s get to it!

Part One: Reflections on starting a book well.

For this mini reading challenge I chose Black Water by Joyce Carol Oates. I wanted something short because I have a few other books I need to get to for the FictionMatters Literary Society. I also liked the idea of reading an author I’ve read recently because, for me, part of reading well is an attempt to contextualize. Contextualizing a book can mean many, many different things (which we’ll get to next week) but I was genuinely curious about how Oates’ writing and themes have evolved over her decades of work so it was an easy pick. Which isn’t to say that the choosing itself was easy! As soon as I announced that I’d chosen this book, I thought of another book I wanted to read instead. Now, I’m in charge of my own reading life and I could have called an audible. But something that makes my reading feel off is when I can’t fully settle into what I’m reading because there’s an itch in the back of my mind reminding me of all the other books I’d like to read. Rather than waffle, I made up my mind to be decisive and stick with my plan—and that was absolutely the right decision. While I do think of myself as a mood reader, overthinking what I’m going to read next causes me to read less overall and be less satisfied with the books I do read. It’s likely that planning out my reading would greatly improve my reading life, so that’s something to consider. I also need to keep reminding myself that reading well starts with actually reading the book.

Lesson 1: Just read the book.

I started Black Water after finishing a very close read of The Last Samurai by Helen DeWitt. I was prepping a comprehensive Book Club Kit for The Last Samurai so I was reading slowly and carefully, stopping to make notes and ask questions often. For Black Water, I wanted to read the book well without reading it quite so closely. I decided to read with pen in hand, but without tabs. I love using tabs when I’m going to need to refer back to passages, but they can really slow me down, particularly when I’m color-coding. For me, reading well does mean reading deeply, but I also want to avoid getting bogged down in a book. I want to notice and reflect, but I also want to keep turning the pages.

Lesson 2: Minimal notes make for better momentum.

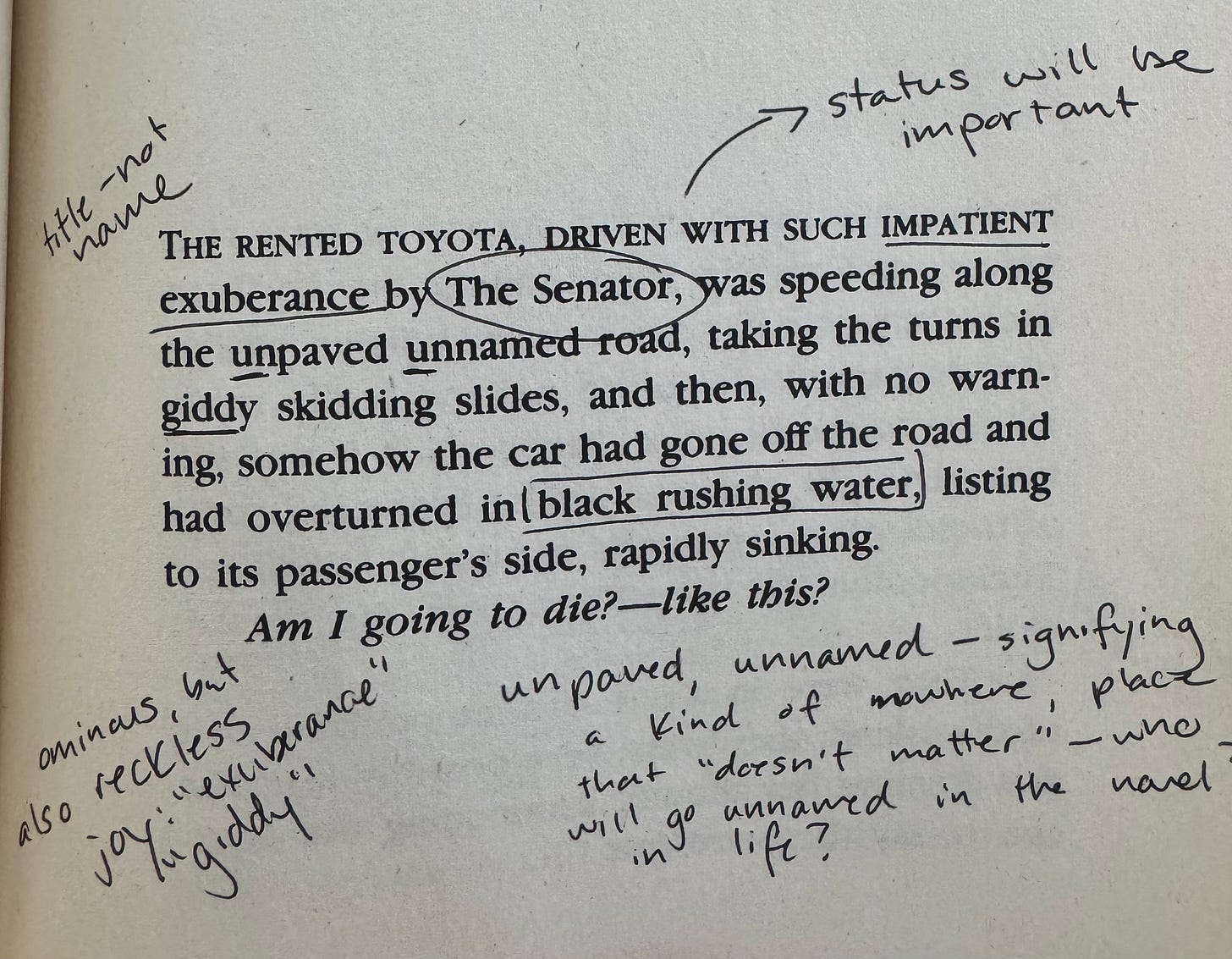

In an effort to keep my notes to minimum throughout the book, I front-loaded my annotations, really trying to pay attention to what Oates was clueing me in on rather than going in with preconceptions. On the first page of Black Water, the phrase “unpaved, unnamed” jumped out at me as did the use of the title “The Senator” rather than a name to refer to the driver of the car. This made me think that names, what goes unnamed, status, and who is known versus who is unknown might all be interesting ideas to pay attention to as I read. Additionally, after reading the first two chapters, I realized that patterns and repetition were going to be a big part of the book. I decided to keep underlining some of the phrases that get repeated throughout.

Lesson 3: Let the book teach you what to pay attention to.

Once I started reading Black Water, I was hooked. Now, I happen to have chosen a very short, very propulsive book for this challenge, but I almost always find that when I commit to reading well, I end up reading faster. This isn’t to say that my reading speed per page is faster than when I’m breezing through a book, but I do tend to finish the books I read well in fewer reading sessions and fewer days. Once I sink into a book, I’m more likely to get invested and make time for it. It almost feels like magic. I can get in my head and expect that reading well will feel more like work and take up too much time, but it’s actually the opposite. I find more joy in my reading when I increase my focus; I read faster, better, and happier to boot.

Lesson 4: Reading well isn’t a slog.

Questions for you:

Feel free to answer these in the comments below or just think about them for yourself!

How did you go about starting your book well? Did you wait for a particular time of day or a solid chunk of reading time? Are you annotating or focusing on momentum?

What have you learned about reading well and yourself as a reader at this point in the project? What does starting well look like for you?

What patterns, stylistic elements, structures, and big ideas have you noticed in the early pages of your book? What is your book asking you to pay attention to as you read?

Part Two: Considering themes and exploring purpose.

If there is one dead horse I love to beat it’s the importance of considering what a book is trying to do rather than judging it for what we readers want it to do. Now I don’t think it’s necessary to do this with every book, and I think there’s plenty of room for talking with other readers about how a book failed to meet our expectations. But to read a book well, I have to consider what goals the book is trying to achieve because, for me, reading well is the internal conversation I’m having with the book.

Consider theme.

Theme can be a loaded term. We throw it around willy-nilly but it’s actually quite a difficult term to define. Additionally, many authors don’t want readers to reduce their work to a single thesis statement. This means talking about theme can get pretty messy, but I love reading for theme because it is my way of making meaning and having that ongoing dialogue in my mind.

But back to definitions. We often think of themes as the ideas that recur in a piece of literature (ex. themes of love, redemption, power, identity, etc.). This is a perfectly fine way to define theme, but for deep reading, I find it incomplete and kind of boring. To really get into a theme, I like to take my list of idea words and ask, “what is the book saying about this idea?” To me, the book’s commentary on or questions about a big idea are the themes. This can trip people up because we get English class flashbacks and worry about finding the “right” answer, but for the purposes of this reading challenge, all I want you to do is consider the question.

Now that you’ve started your book, let yourself notice the big ideas that the author is exploring. Here are some of the ideas I’ve noticed in Black Water: names, status, power, sex, agency, gender dynamics, story-telling, politics, class, and obsession.

Next, as you continue to read, ask yourself what the book is saying about any of the ideas you’ve noticed. Again, you do not need to have an answer at this point—or ever, really. But asking the question will help you go from a surface level noticing to a deep exploration of what this particular book has to say about a universal idea. The midpoint is a great time to start asking the “what is this book saying about X” question because you can begin paying attention to possible hints and answers. One tip if you get stuck is to consider how two or more of your ideas are connected within the novel. Sometimes it’s harder to start thinking about a more open ended question and linking a couple of ideas sharpens the question and provides focus.

Her are some examples of questions I’m asking about Black Water: What is this book saying about different types of power? How do gender and status impact power? Can sex be a means of gaining power or is it always a loss? How is this different for men and women? What is the difference between class and status within the world of the novel?

I don’t have answers for these yet, and the book might not have answers either! But now that I’ve posed the questions, I’ll be primed to notice anything that gestures towards a possible answer or a deepening of my understanding.

Add friction.

If theme is a struggle for you or posing these kinds of questions just isn’t the way you like to engage with books, another method I like is adding friction. By this I mean finding an idea your brain can work with and against as you try to identify a novel’s purpose. Put even simpler: consider someone else’s ideas about your book. One way to do this is to talk to someone else who is reading or has read the book. Another is to read reviews and criticism about your book and then consider whether you agree or disagree with what you read.

Here’s an excerpt from the Kirkus review of Black Water:

She is the one, the one he's chosen, Kelly tells herself, frightened though she is as the Senator speeds down a dark, unpaved road toward the ferry, sloshing a fresh gin-and-tonic on her dress. But when his car flips off the road and into the black, polluted Indian River, Kelly gradually realizes that her assumption is false: she isn't chosen, at least not for rescue—and her brief life, with its half-understood longings, fears, and dreams, is over almost before it has begun.

I’m very intrigued by what this reviewer has flagged about the idea of being “chosen.” This isn’t a concept that leapt off the page at me while I was reading, but I can definitely see how they arrived there. Now as I read I’m going to continue to consider what this novel is saying about being chosen, whether I think that’s a major theme of the work, and how the idea of being chosen might interact with the other big ideas I’ve identified in my reading.

Goals beyond theme.

As is probably clear, I like to read for theme. I love to consider the overt and implicit ideologies at work in a text and unpack those, and the books I tend to love are often books that take thematic questions seriously. But you can consider what a book is trying to do without being especially interested in theme. Here are some other ways to consider a book’s goals and some questions to ask about your book1:

Narrative goals: What story is the book telling? What makes this story important or compelling? How is it similar to other narratives you’ve read? How is it doing something different?

Structural goals: How is the book organized? Is it more traditional or inventive? What effect does the organization have on your reading?

Perspective goals: Who is telling this story and why does it matter? What perspective is the book offering that might be new, innovative, or important?

Emotional goals: What is the book trying to make you feel? How is it working towards that end?

Pacing goals: Does the book want to slow you down or speed you up? Is it trying to keep you on the edge of your seat or would it rather you slow down and savor?

Educational goals: What is this book trying to teach you about a particular topic, time period, person, etc?

Aesthetic goals: What about the book is beautiful or artistically interesting?

Contextual goals: What ideas, events, or other texts is the book responding to? What is it subverting, calling into question, or offering a new take on?

As you continue to read, consider asking some of these questions about your book. I will reiterate (because this is so so important to me) that coming up with the “right” answer to any of these questions is not the point. In reading well, answers are less important than questions. Simply asking yourself some of these questions will allow you to get deeper into your text and notice things you wouldn’t notice otherwise.

Questions for you:

What big ideas ideas have you noticed in your book so far? What questions are you asking about these ideas?

What other goals do you think your book is working towards?

Thanks for playing along with me! I can’t wait to hear what (and how!) you’re reading!

For questions, comments, or suggestions, please don’t hesitate to reach out by emailing fictionmattersbooks@gmail.com or responding directly to this newsletter. I love hearing from you!

This email may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase through the links above, I may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you.

If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, please forward it to a book-loving friend. That’s a great way to spread bookish cheer and support the newsletter!

Happy reading!

Sara

I completely made these up based on what I like to think about in my own reading. Feel free to rename, add-on, or forego them completely.

I'm reading James which was on my TNBR pile. I was sure I could read it in two weeks. I haven't anotated since school and I'm a fast reader of many books and genres. I'm getting such a lot from annotating, checking references and looking up words and phrases I didn't know, which I would usually skim over! I've learned such a lot about the roots of slavery and the reasoning (infallable) for its' continuance. I'm reading and understanding James as a satire, with the author's reference to Candide as a clue. I found some chapters weak but I've also started The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as background material.

Throughly enjoying learning new things and exercising my brain with this challenge.

I'm re-reading Ithaca by Claire North (first time reading in print, I initially listened to the audio), and it's been great. There is a huge emphasis on gender, the power differential between men and women, and how women use subversion to exercise power. I'm still working out exactly what the author is saying about all of these themes.

Hera - the queen of queens, women, and mothers- narrates and story, and I'm noticing how often she references the stories and people the poets will immortalize compared to the story she's telling.

I'm already in the habit of marking passages or lines that stand out as especially important or beautiful, but I'm trying to expand my critical reading and notations by asking myself more questions along the way.