In a recent Reading in Public, I shared about my current affinity for short fiction, what I look for in a short story, and a few of the questions I ask when reading shorter works.

Reading in Public No. 21

Last week I had the pleasure of sharing a Q&A with debut author Kelsey Norris. Kelsey’s collection of short stories House Gone Quiet works in the way I like my short stories to work, carefully leading the reader through a series of questions and revelations and landing in a place that makes you say simultaneously, “what?!” and “ohhhh…”

Today, I’m going to walk through how I apply those question to an actual story. Way back in Reading in Public No. 1, I shared that part of my inspiration for this series was a grad school professor who advocated for modeling reading to students. His claim was that once we learn the basics of reading, we don’t get much active reading instruction. He also believed in the benefits of observing the way another reader’s mind works. I completely agree with this assessment. While we often talk with other readers about books and stories after we read them, we rarely—if ever—get to see how another person reads.

This is a much easier task to perform in person, but I’m going to try to share my thinking through a short story using the five questions I outlined in last week’s post.

“Labyrinth” by Amelia Gray

This newsletter will be most interesting to you if you’ve read “Labyrinth” by Amelia Gray. It’s about a 15 minute read, and you can find the story here. If you enjoy the story, consider purchasing Amelia Gray’s speculative collection Gunshot.

1. What expectations is the author establishing?

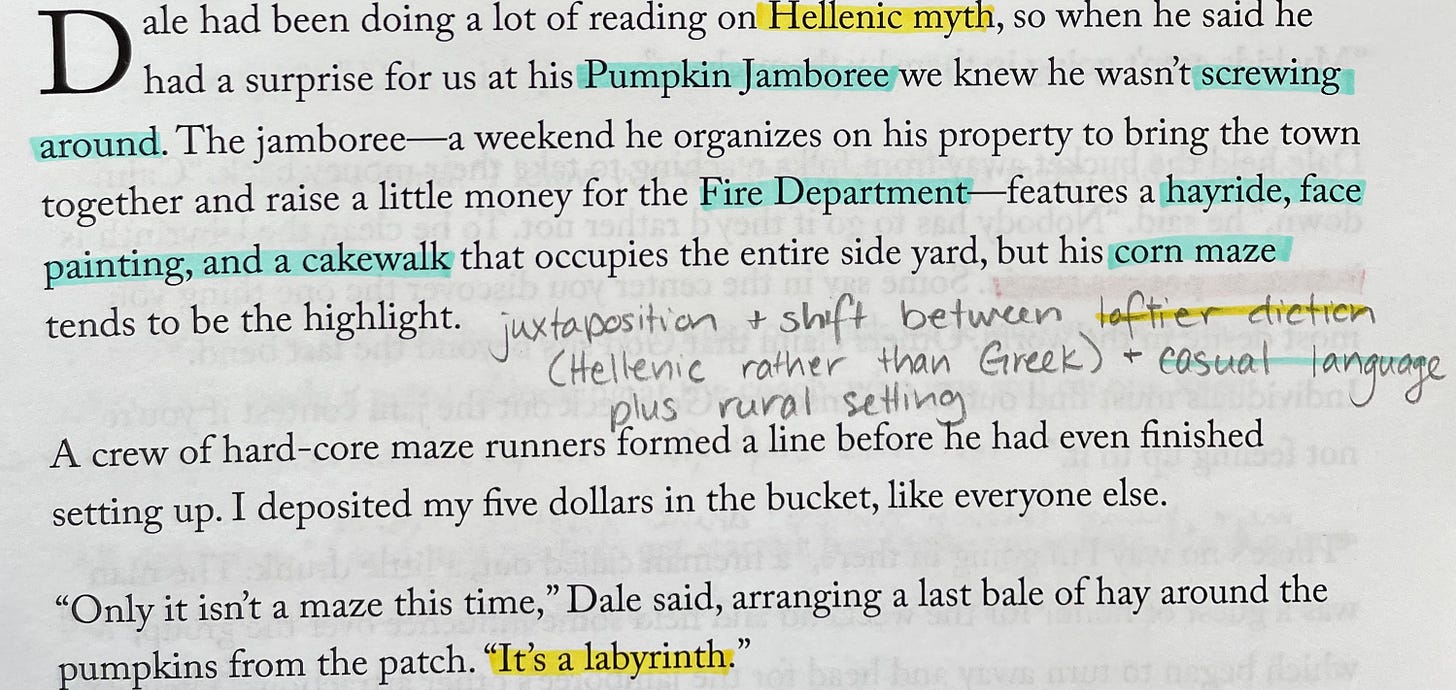

The first line of “Labyrinth” is fantastic and immediately gives us a sense of what we’re in for: “Dale had been doing a lot of reading on Hellenic myth, so when he said he had a surprise for us at his Pumpkin Jamboree we knew he wasn’t screwing around.” The immediate juxtaposition between the phrases Hellenic myth, Pumpkin Jamboree, and, even, screwing around, hints at the tonal shifts Gray will use throughout the entire story, oscillating between formal, lofty, almost archaic references and the casual language of the small town setting. The story feels grounded in realism, even if Dale himself is interested in mysticism.

In the first couple of pages, Gray also establishes expectations about who I’ll call our two main characters: Dale and Jim. Dale is hardworking, putting “hours of lost work” into this labyrinth that no one wants to enter. He’s also erudite, using terms like “unicursal,” and perhaps superstitious, telling the gathered crowd that “the labyrinth is known to possess magic.” Jim, although he’s our narrator, is a bit more of a mystery. We know that Dale admires his “pluck” for agreeing to enter the labyrinth first. We also know that he is lonely, perhaps hinting at his motivation for entering the labyrinth in order to be a good friend to Dale.

2. When and how are they subverting those expectations?

We get a break in the tone in the third page of the story when Jim tells us he doesn’t want to go home because it’s lonely “and the tap water had begun to taste oddly of blood.” While it is unclear what, if anything, this detail will have to do with Jim’s journey into the labyrinth, it is the first time we get any imagery that feels truly like a horror story.

Gray subverted my expectations of where the plot was headed whenDale gives Jim the Phaistos Disk to carry into the labyrinth. So many details up until this point feel mundane—easy to picture at any small-town festival. While the moment with the Disk is funny (Jim thinks it’s a trivet for hot dishes), it’s also the first truly bizarre moment.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, our initial understanding of Jim is challenged when he hears the crowd talking about him through the walls of the labyrinth. We learn that something happened at last year’s jamboree that has turned Jim into a community laughing stock. While brave might not have been our go-to descriptor for our narrator prior to this conversation, the revelation that he is considered cowardly by his peers alters our understanding of his motivations and allows for new speculation on where this story might be headed.

3. What patterns to I notice? Where do I see breaks in those patterns?

As mentioned, the patterns in word choice throughout this story are established early. Gray intersperses occasional lofty, scholarly terms—mostly relating to myth—throughout a story that feels (mostly) grounded in the reality of small-town life, complete with fairly casual diction and dialogue. The alternating diction adds a lot of humor to the story. The establishment of such a consistent pattern also allows for the moments of horror and otherworldliness to stand out in contrast.

4. Where is the story leaving me?

[Spoiler alert!] Like so many of the short stories I love, I could describe this ending as both definitive and open-ended. It concludes with a bang that’s easy to interpret, but, as a reader, my mind can’t help but wanting to fill him more details.

I love the last moment of this story because it leaves us both someplace completely new and right back at the beginning. In the final paragraphs of the story, we firmly enter the realm of horror…mythical horror. Jim has lain down in his own grave, having been lulled by the praise he hears from the crowd (“the one thing [he] most desire[s] in the world”) and being pressed further into it by the “trivet” he can’t release. Nonetheless, Gray continues to insert humor and casual quips to remind us of where we began. And, quite perfectly, the story closes with Jim meeting “the minotaur,” landing us right back at our opening sentence and Dale’s affinity for Hellenic myth, almost as if we ourselves had entered and swept through our own unicursal labyrinth.

5. Why isn’t this a novel?

In the case of “Labyrinth,” this seems pretty straightforward—there’s not enough character or plot to carry a full novel, and the legend-like feel doesn’t warrant it. I am intrigued, however, by just how brief this story is. There’s nothing wasted here—Gray builds a complete world and hits so many emotions in so few pages. There are, of course, many question to be answered at the end, but that seems to me to be the joy and the fun of reading any eerie story.

For more short story exploration, subscribe to the Novel Pairings podcast where we host book club style conversations about short fiction on the podcast regularly. Our most popular discussions include “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson, “Roman Fever” by Edith Wharton, “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “The Fall of the House of Usher” by Edgar Allan Poe, “Speech Sounds” by Octavia Butler, and “The Prairie Wife” by Curtis Sittenfeld.

Reading in Public deep dives are supported by paid subscribers to the FictionMatters Newsletter. If you enjoyed today’s topic, please consider buying me a coffee or becoming a paid subscriber. If a financial contribution isn’t right for you, please forward this email along to a reader friend. That’s a great way to help FictionMatters grow and stick around. Thanks for your support!

For questions, comments, or suggestions, please don’t hesitate to reach out by emailing fictionmattersbooks@gmail.com or responding directly to this newsletter. I love hearing from you!

This email may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase through the links above, I may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you.

-Sara

I just read #1 of your questions without reading the story & I definitely want to read the short story before I continue on - but I have to say it’s so interesting to see how your mind works when reading just the first sentence!

What a great story! I really felt the tension building as it went along.

Thanks so much for sharing your reading questions. I haven’t done that kind of close reading in a long time and I’m learning a lot from you and from Chelsey this year :)