Reading in Public No. 16: Long books, active attention, and CoComelon

What do readers owe long books?

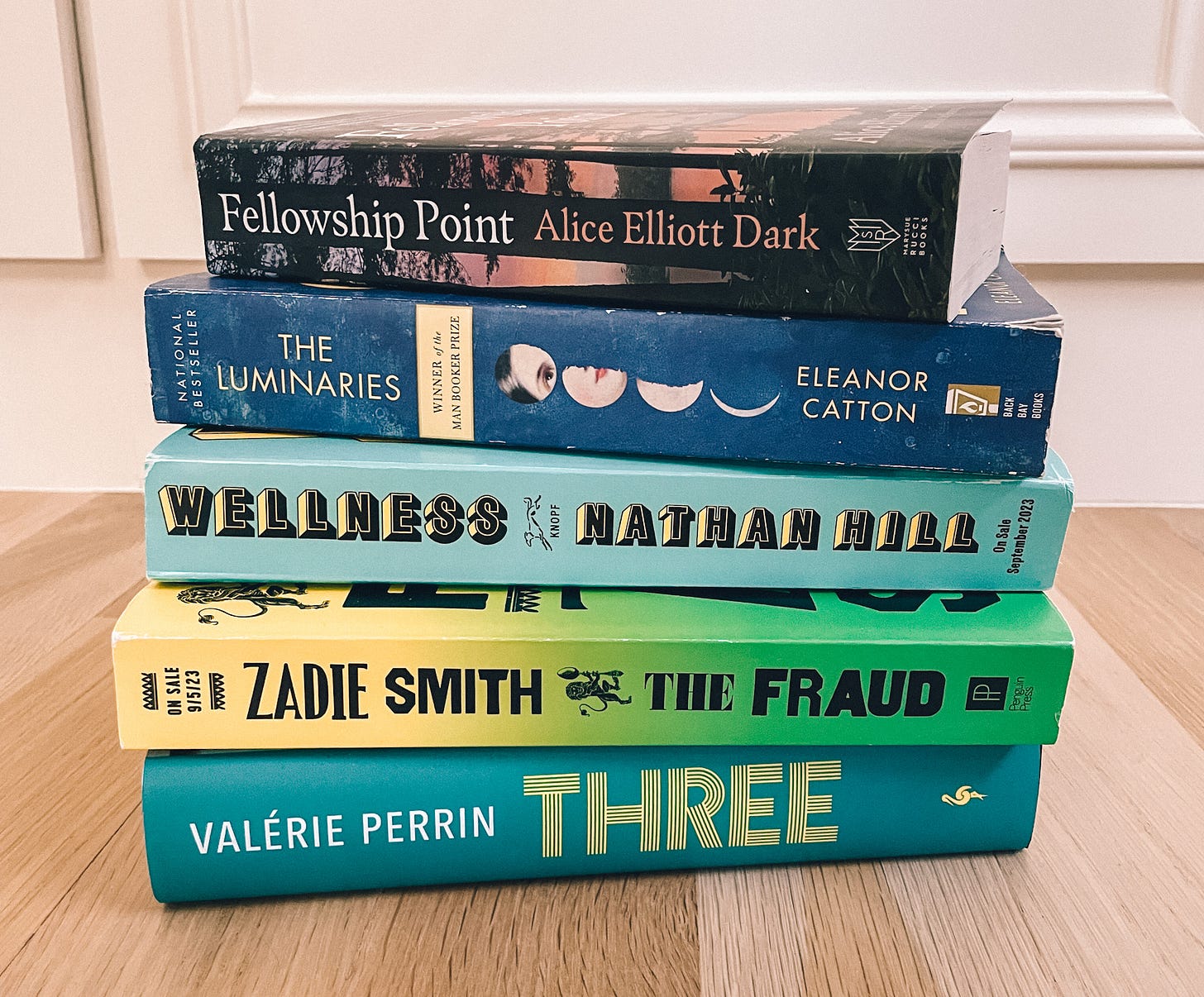

2023 has been my year of Big Books. This began when I started Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries (my third attempt) in December of last year and finally finished it in February. Since then I’ve read Fellowship Point, Birnam Wood, The Parisian, Three, The Fraud, and Wellness—all books over 500 pages—and I have quite a few hefty tomes I’d still like to get to this year.

Not every long book has been an all out favorite, but each one has been a memorable reading experience, and I find myself continuing to reach for these chunky books in spite of the amount of time they take and the number of neglected books on my lengthy TBR. Yet while I have loved the time it takes for me to read these books, I find myself itching to give caveats, warnings, and assurances when I recommend them to other readers. My reviews of these books are peppered with phrases like “it reads fast,” or “you won’t feel the page count,” or “it really picks up,” or “you can skim through the tangents.” And while I think this information is quite valuable for potential readers, this language is also subtly communicating the idea that faster, leaner, tighter books are somehow superior—and do I really believe that? Is a story hacked down to only what’s “necessary” really a better story?

Don’t get me wrong, some books need a firmer editing. There may be plot lines, tangents, characters, or extraneous descriptions that distract and detract from what the author is intending to do. But I’m beginning to suspect that my complaints about long books and what I feel is “necessary” to a story are more often than not a me problem.

While I once loved poring over the pages of a classic, unfurling sticky periodic sentences and pondering multiple meanings of words, my attention span has atrophied and I’ve started believing that it’s the book’s role to keep me gripped rather than my role to actively attune my attention to a novel. Of course I love a book that hooks me from the first line and gives me that nostalgic up-all-night, one-more-chapter feeling, but I want to resist the idea that a book is failing if I find my attention wavering or if it takes its time arriving at its final destination.

And this brings me, once again, to this Ezra Klein Podcast episode with Maryanne Wolf. I wrote about it here before when I set my slow reading intention and the entire episode explores this idea of active attention. But the part that keeps popping into my mind now is when Ezra brings up the New York Times’ reporting on the making of CoComelon. If you’re not familiar, CoComelon is a wildly popular, frighteningly addictive show for toddlers produced by Moonbug—a British company responsible for a slew of popular kids shows.

The revelation Ezra references in the podcast episode is about how Moonbug researchers test their product—and it’s downright dystopian. Before release, CoComelon episodes are shown to 2-year-olds while boring distractions take place around them (ie an adult pouring coffee or acting out household chores). If the toddler looks away from the CoComelon episode and at one of these mundane scenes, that timestamp is flagged and the show creators add more oomph (like a faster scene cut or some other piece of visual sugar) to ensure utter toddler absorption.

As the mother of a toddler, I can appreciate the necessity of something like CoComelon as a survival strategy and something that brings kids joy. More than an indictment of children’s cartoons, the CoComelon revelation made me reflect on how I as an adult consume my entertainment. These days I sometimes approach my reading with the expectation that the onus is on the book to draw me in and keep my attention, rather than thinking of myself as actively bestowing my attention on that given book. If a book doesn’t add oomph when my mind starts wondering, I’m tempted to see that as a flaw.

But I don’t need my books to be CoComelon. For my personal idea of a great read, I’ve decided it’s okay if I’m a little bit bored for part of a book. It’s fine if my attention wavers. Mid-book lulls, authorial tangents, and extraneous details are welcome. I want to lean into books that ask me to exercise my active attention.

And maybe right now you do want your books to be CoComelon. Who doesn’t need a distraction that helps us forget both the mundane and frightening aspects of the real world? Who doesn’t love an author who can hold us in their grasp from cover to cover?I certainly welcome that experience as well! But I do hope we readers can resist the idea that a book’s merit lies in how easy it is to get through.

In a beautiful essay about what makes a good reader, author and teacher Vladimir Nabokov compares writing a book to climbing a mountain.

“…[the] mountain must be conquered. Up a trackless slope climbs the master artist, and at the top, on a windy ridge, whom do you think he meets? The panting and happy reader, and there they spontaneously embrace and are linked forever if the book lasts forever.”

After years of teaching exhaustion, pandemic fatigue, pregnancy brain, and new baby business, I think I’m finally ready to do the work required to put in the work to be that “panting and happy” reader once again.

Reading in Public deep dives are supported by paid subscribers to the FictionMatters Newsletter. If you enjoyed today’s topic, please consider forwarding it to a friend, buying me a coffee, or becoming a paid subscriber. Thanks for your support!

For questions, comments, or suggestions, please don’t hesitate to reach out by emailing fictionmattersbooks@gmail.com or responding directly to this newsletter. I love hearing from you!

This email may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase through the links above, I may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you.

-Sara

if you haven’t already, check out Brandon Taylor’s latest newsletter addressing the idea of extraneous detail in books. i really enjoyed it! he suggests that most of what we label extraneous is actually important to the work of art and its overall commentary/point of view, having been chosen by the author for inclusion for a reason. and similarly to what you’re saying, just because you don’t feel gripped by that portion of the text or even feel bored by it doesn’t indicate that the thing you don’t like as much is pointless.

Holy guacamole I love this